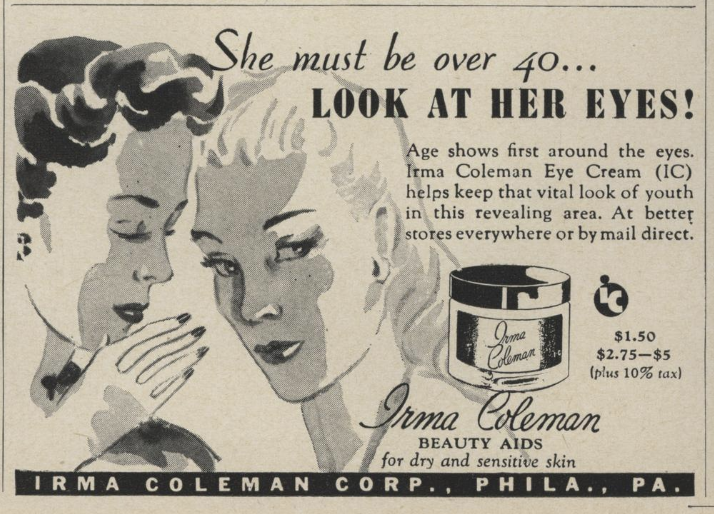

Item 1: “She Must Be Over 40…”

This striking beauty ad captures the age-anxieties and gendered expectations of mid-20th-century American women. The provocative headline, “She must be over 40... Look at her eyes!”, weaponizes age as a flaw, reinforcing a cultural narrative where youth equals beauty and desirability. Wrinkles aren’t just signs of time passed—they’re painted as warnings, as evidence of a woman’s declining worth.

The advertisement's focus on eye wrinkles highlights a common fear that marketers capitalized on with targeted products like Irma Coleman Eye Cream. Here, the product is framed not simply as skincare, but as a remedy for aging itself—particularly in a “revealing area” like the eyes. This reflects a broader trend in which beauty advertising pathologized natural aging, especially in women, and sold consumerism as the cure. Priced from $1.50 to $5, the cream was likely considered a premium item at the time, subtly suggesting that preserving beauty was a luxury—but also a necessity worth the cost.

The stylized illustration of two women in hushed conversation drives home the pressure: aging wasn’t just personal, it was social—something visible, something judged. Irma Coleman’s branding as a specialist in “beauty aids for dry and sensitive skin” further demonstrates how companies cloaked their products in medical-sounding authority, creating trust and urgency. In this way, the ad doesn’t merely sell eye cream—it sells a dream of youth and the fear of aging out of society’s favor.

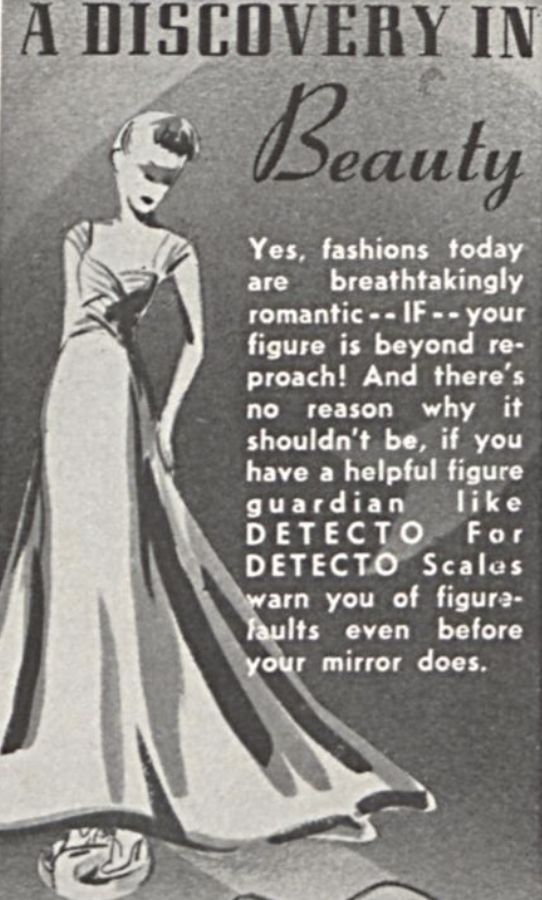

Item 2: “A Discovery in Beauty”

This advertisement for Detecto bathroom scales reflects mid-20th-century America's growing obsession with feminine beauty and body image. Marketed with the allure of glamour and technological progress, the scale isn’t just a household item—it becomes a symbol of discipline, virtue, and desirability. The tagline, calling it a “figure guardian,” implies that one’s weight must be vigilantly monitored, as though a woman’s value depends on her ability to control it.

By pairing the scale with a “free charm box” and a reducing system designed by a so-called beauty authority, the ad directly links physical appearance with femininity and consumerism. These “bonus” features reinforce the idea that beauty isn’t something natural or self-defined—it’s something you earn, maintain, and purchase. In this postwar context, where domesticity and perfection were idolized, even health and technology became tools of aesthetic conformity.

Detecto’s claim of “over 3,000,000 in use” reflects the normalization of this behavior. Scales moved from doctor’s offices into private homes, becoming part of daily life for millions of women. The line between health and beauty blurred, and with it came a subtle but powerful moral imperative: control your body, and you control your worth. In this light, the ad isn’t merely about a product—it’s a prescription for how to live, wrapped in a pretty promise and quiet pressure.

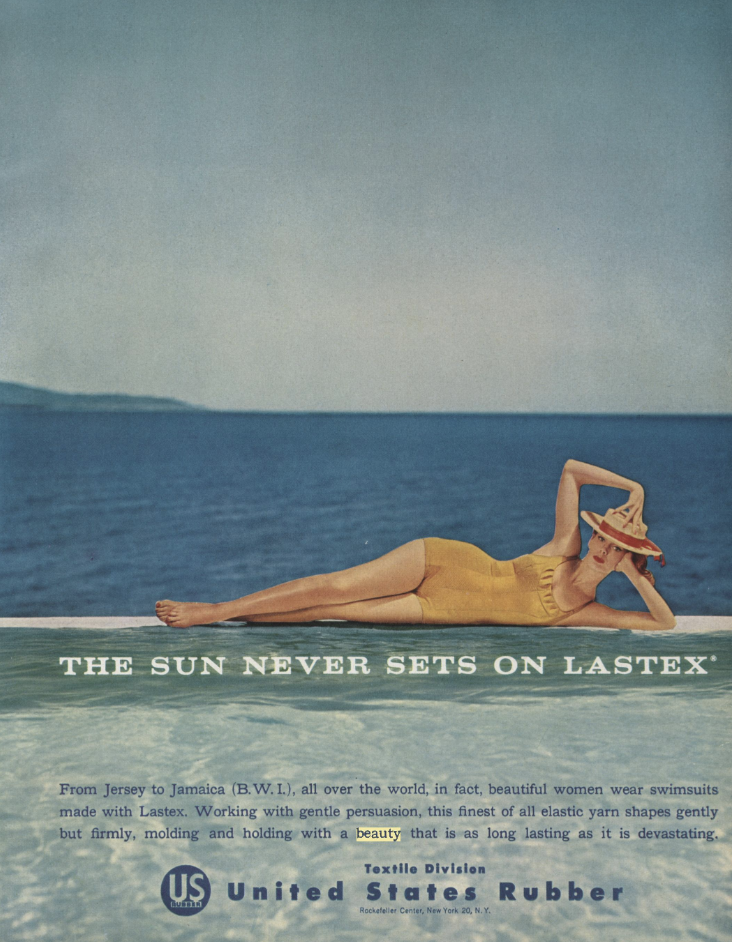

Item 3: “The Sun Never Sets on Lastex”

This 1950s advertisement for Lastex, a synthetic elastic fiber made by United States Rubber, exemplifies the way women’s magazines and commercial media constrained ideals of femininity in mid-20th century America. The image portrays a slender, tanned woman reclining beside the pool in a figure-hugging swimsuit, framed by the tagline, “The sun never sets on Lastex.” With its glamorous aesthetic and exotic backdrop, the ad presents a fantasy—one that ties beauty, leisure, and desirability to consumerism.

Magazines frequently published such images, encouraging women to strive for narrow and often unattainable beauty standards. These publications marketed perfection as a matter of discipline and purchase, implying that with the right products—like Lastex swimsuits—a woman could mold herself into societal ideals. In doing so, they contributed to widespread body dissatisfaction and reinforced the notion that a woman's value was tied to her appearance.

Beyond individual impact, these messages upheld a broader cultural norm: women as passive objects of beauty and consumption. The damage went far beyond the pages of magazines, influencing generations of women and shaping societal expectations in ways that still echo today.

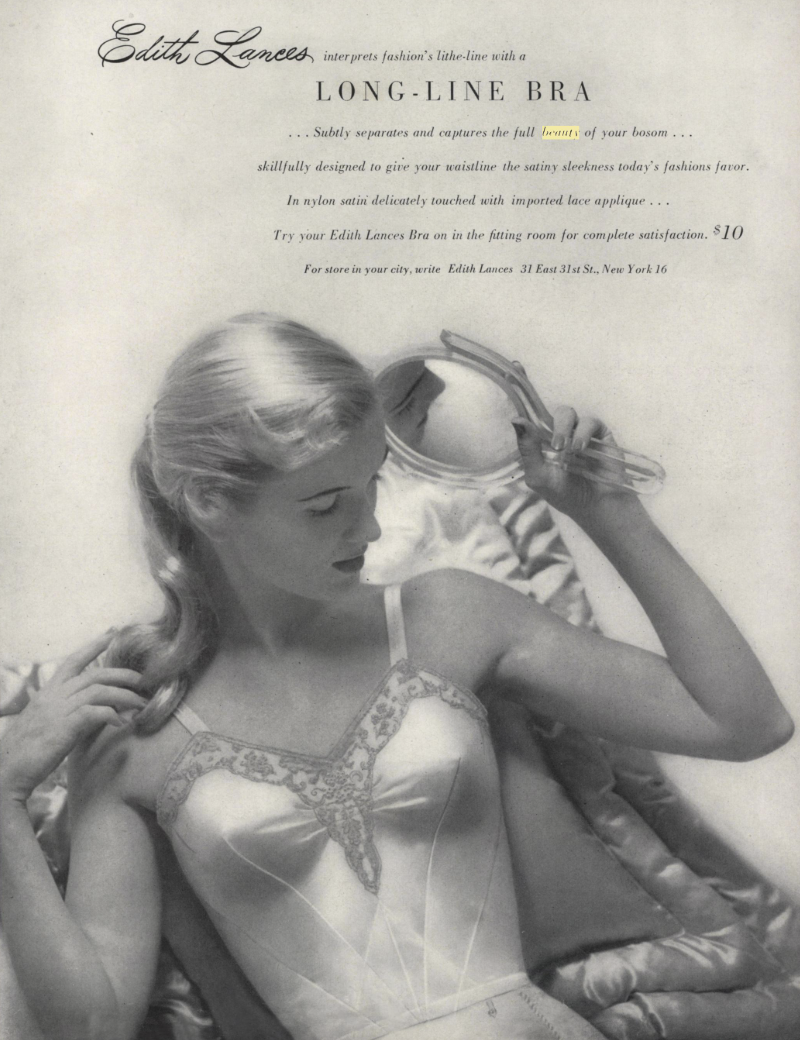

Item 4: “Edith Lances Interprets Fashion’s Lithe-line…”

This advertisement for an Edith Lances "Long-Line Bra" highlights the mid-20th century obsession with reshaping the female body to meet rigid standards of beauty. Promising to “subtly separate and capture the full beauty of your bosom,” the ad equates bodily conformity with elegance and self-worth. The model, posed in a satin bra and surrounded by soft textures, reflects the era’s ideal of femininity: passive, poised, and physically molded to perfection.

Such images were staples of women’s magazines, where editorial content and advertising often blurred. These publications cultivated a worldview in which femininity was constructed through disciplined self-presentation and the constant pursuit of ideal proportions. Products like this bra were marketed not just as undergarments, but as tools of transformation—solutions to perceived flaws, selling the idea that beauty could and should be engineered.

By reinforcing narrow definitions of womanhood and bodily beauty, advertisements like this contributed to a culture of inadequacy. They taught generations of women that their natural bodies required correction, that comfort was secondary to contour, and that femininity was a performance sustained through consumption.

-

Advertisement: Nutrine (middlebrooke lancaster, inc.). (1943, Dec 15). Vogue, 102, 76. Retrieved from https://utk.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/magazines/advertisement-nutrine-middlebrooke-lancaster-inc/docview/879230150/se-2

Advertisement: Detecto scales, inc. (detecto scales, inc.). (1939, Nov 01). Vogue, 94, 114. Retrieved from https://utk.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/magazines/advertisement-detecto-scales-inc/docview/879216393/se-2

Advertisement: Us (us). (1959, Dec 01). Vogue, 134, 55. Retrieved from https://utk.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/magazines/advertisement-us/docview/897861051/se-2

Advertisement. (1949, Nov 15). Vogue, 114, 47. Retrieved from https://utk.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/magazines/advertisement/docview/911886305/se-2